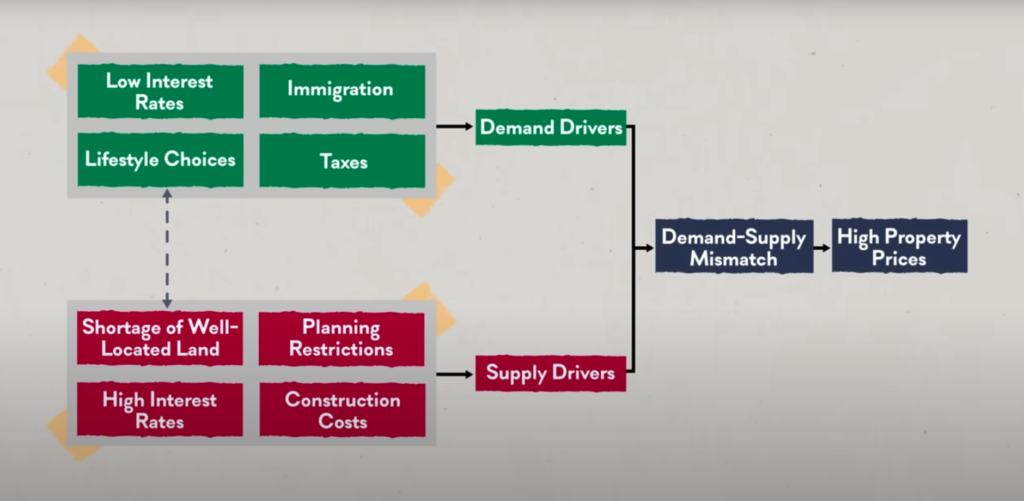

There are demand factors and there are supply factors that together contribute to the housing affordability crisis that many everyday Australians are experiencing today.

In this post, we turn to the supply side of the equation and look at how the supply has simply not kept up with the demand for property, hence driving up house and unit prices.

The Supply Drivers of Housing

The 4 key drivers impacting the supply of residential accomodation are the shortage of well-located land, planning regulations, interest rate rises and high construction costs. These are all big issues that are all worth a post by themselves, but we will try to keep it succinct here.

1. Shortage of well-located land

Now here’s the thing: Australia has an abundance of resource-rich land. But, we actually have a stark shortage of well-located land.

In other words, the land located where we all want to live – near services, infrastructure, communities, amenities, and most importantly, jobs – is in very short supply.

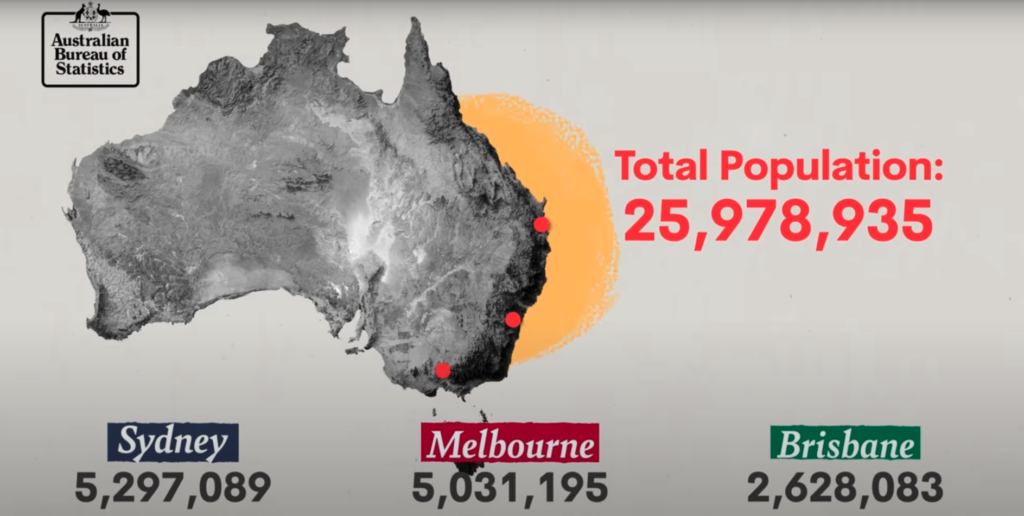

Let me put it this way: over 50% of Australia’s population live in its three major cities, Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane.

If we compare this to the UK, where 50% of its population is spread across 9 of it’s largest cities; or the USA where half the population live across 36 cities – it’s really unusual.

Part of the problem also lies in the fact that our cities have so many geographical constraints.

Sydney is a prime example of this: it’s landlocked between its eastern side by harbours, bays and beaches and its western side by the Blue Mountains.

Another factor, which we discussed in our last post (demand driver) and that is linked to the shortage of well-located land is our cultural demand for “space” and “lifestyle”.

We have a general tendency to resist “vertical living” within the city centre – with many preferring the lifestyle of middle-ring and outer ring suburbs. This has led to an aversion towards high-density living, which means cities are much more spread out compared to our overseas counterparts. And of course without more density, and only so much “liveable” land, we drive the demand up along with the property prices.

What also happens is that the land component of property becomes more valuable – driving the prices up even further. You can see this by looking at the massive difference in the increase in the price of houses versus units.

Over a 30-year period, house values in Australia’s capital cities have increased by 4.5 times to nearly $930,000, while unit values have only tripled to just over $635,000.

If we compare this to the less populated regional areas, the figures are slightly different, but it paints the same picture:

House prices have tripled to around $623,000 and unit values have doubled to around $520,000 over the same period.

And I’m sure it comes at no surprise that the growth in land value has far exceeded the growth in incomes.

It takes on average about 10 years to save up the 20% deposit, which, by the way, is 1.5 times the average full-time earnings. Whereas in 2001, it would’ve taken you around 6 years.

And if I add another layer to this and look at the stats in relation to the higher interest rates, the national estimate of median income required to service a new mortgage is now at a record high of 45.5% of income, compared to an average of 34.5% in 2010.

So, no – you’re not just imagining it. It is most definitely more expensive to buy a house today, than it was 10/20 years ago.

But, the harsh reality of it is that high property prices are also as a result of the choices we make as a society. Our government, which we vote in, have all made certain choices that have led to high land and house costs.

2. Planning Regulations

One of the loudest complaints at the moment is that new land releases are just too slow.

Although $37 billion worth of new land was released across Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria last financial year, demand is still far overtaking supply.

Settlements on new residential land have dipped 13.6% to 73,901 dwellings this financial year, with average time to settle vacant land taking on average 275 days in NSW and over a year in Victoria.

It doesn’t help that new land releases sell like hot cakes because families and first home buyers find it more attractive to build and customise their own home rather than buy an established inner-city home or apartment.

In the the three LGA’s of Camden, Blacktown City and Liverpool City alone, a shortage of 4,276 dwellings are forecasted over the next 5 financial years despite significant new land releases.

And the only way to bridge this gap is to build new apartments.

But the issues don’t stop there. To add even more fuel to the fire, planning approvals for high-density and medium-density developments at a local government level are heavily bottlenecked and painfully slow.

The reason? NIMBY resistance.

Local and established property owners frequently resist and oppose new planning approvals by effectively saying “Not In My Back Yard”.

In fact, approval rates have dropped nearly 35% over the last year and over 50% over the last decade.

So, basically, those with property are keeping those without out of the market – essentially keeping demand, and consequently prices, high.

Now, pursuing space, and protecting space is one thing, but it’s still not enough to explain all the weight of demand in the Australian property market.

3. Rising Construction Costs

They say “time is money” and nowhere is this more true than the property development world, where each day of project delay can mean thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, in extra costs.

Even if more land can be supplied, or projects approved, the viability of Builders and Developers form a critical part of the value chain to ensure completed properties get delivered on time.

But, more recently, supply from builders and developers have been impacted by a “perfect storm” of cost-related issues – literally.

In 2022, inclement weather caused 20,000 detached dwellings and 8,000 multi-density dwellings to be delayed. Supply chain shocks have caused the price of key building materials and construction inputs to rise by up to 30% for some inputs.

And labour shortages have also dramatically increased construction costs. Since 2021, builders are paying three times more to hire a steel worker, and 50% more to hire a form worker.

So, supply has taken a serious hit with expected building completions down 29,990 for detached dwellings and 15,700 for multi-density dwellings in the last year compared to forecasts.

It also meant that quite a few high-profile builders, like Porter Davis and Chatham Homes, have gone bust because they couldn’t honour their fixed-price building contracts.

4. High Interest Rates

In addition to rising construction costs, high interest rates further throw out the feasibility of new developments – which brings me to the last part of this discussion.

We started with low interest rates and now we’re ending with high interest rates, because at the end of the day it’s all a cycle.

As you well know, we’ve recently seen the steepest increase on interest rates over the last 20 years – and this impacts everyone – from big time property developers to the smallest of first-time home buyers.

Many new developments are have become unprofitable, making it less likely to ever get off the ground.

Existing projects are experiencing higher holding costs meaning they erode the developer’s liquidity, threatening their viability and increasing the chances that they could go under.

And at a household level, high rates are meant to increase the supply of housing stock, as more people are forced to sell, which contributes to falling house prices.

But this hasn’t happened for three reasons:

i) A large stock of fixed rate mortgages, secured at really low interest rates during the pandemic, have delayed the impact of rising mortgage repayments and falling prices.

ii) Borrowing capacities have fallen by more than the reduction in property prices. So, basically, the same income gets you less property than before interest rates started to rise.

iii) Even with lower house prices, deposit requirements still prove prohibitive at current income levels relative to property values.

And this brings us to the end of this housing affordability crisis series. This has been a very deep multi-dimensional topic and a lot of take it. Thank you for staying with us.

In the new year we’ll be bringing you second part of this topic where we will assess the impact of the housing crisis on your Australian households and what you can do about it.