The housing market is fast becoming out of reach of so many families who are looking for a roof over their heads. How did property prices become so high, so quickly?

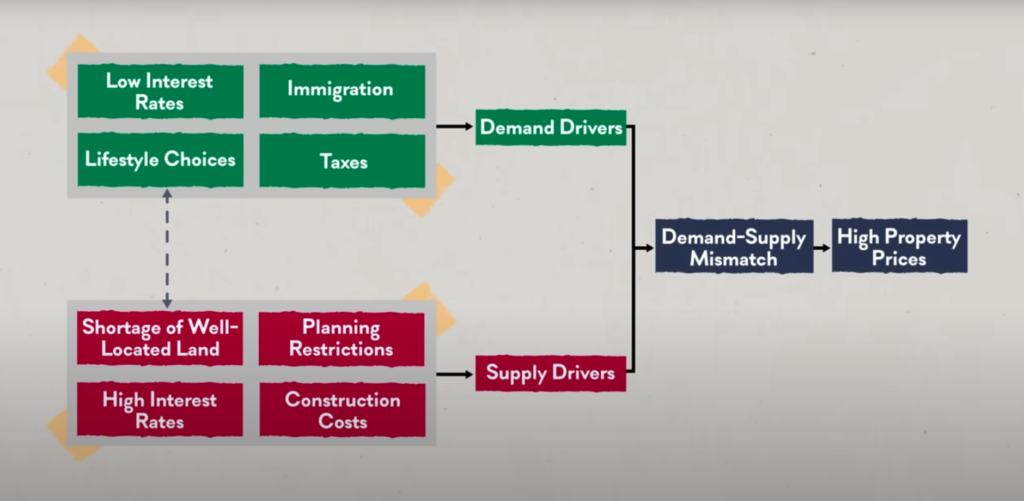

In our housing crisis series, we present the eight factors affecting demand and supply of housing in Australia. They are what’s keeping property prices so expensive and which are preventing many Australians from entering the property market.

We will now look in more detail at the demand drivers – where is the demand for property coming from and how are they contributing towards the persistent rise in property prices.

The Demand For Housing

On the demand side of the equation, there are 4 drivers there, namely, low interest rates, immigration levels, Australians’ lifestyle preferences and our tax regime.

Let’s dive into it.

1. Low interest rates

Low interest rates, or “cheap money,” have been the common scapegoat for why Australian property prices are so high.

And looking at recent history, it’s easy to see why.

Between 2008 and 2022, Australia was in a period of “loose monetary policy,” which means rates were either on the decline or left on hold for months on end.

Between September 2008 and September 2009, against the background of the Global Financial Crisis, the RBA lowered the cash rate from 7.25% to 3.00%. And then, the cash rate remained at 4.75% for most of 2011 before it was lowered to the historic low of 0.10% at the height of the pandemic.

During this same period, the property market soared to more than double in value.

If we just look at the figures during the pandemic period, they tell their own story. Interest rates at a never-seen-before 0.1% and property values are nearly 25% higher than they were before March 2020.

Low Interest Rates Don’t Paint the Full Picture

While most blame the RBA and low interest rates, they don’t actually paint the full picture.

In fact, if we look at property trends between the 1980s and 1990s, interest rates were on the rise, but property prices remained resilient.

And if we look at the current property trends around the world – they’re all experiencing interest rate rises without the massive jump in residential property prices. Many countries also experienced low interest rates, but their house prices did not rise at the same pace as Australia.

And here’s the thing: Central banks, including the RBA, don’t really care about property prices.

It’s not the a Central Banks role to target asset prices. They’re actually only concerned with property prices to the extent that the price rises impact feelings of wealth and therefore household consumption, which is a direct driver of GDP.

Dr. Philip Lowe said it best in his closing remarks as the outgoing RBA Governor: “Interest rates influence housing prices, but they are not the reason that Australia has some of the highest costs of housing in the world.”

2. Immigration Levels

The next demand driver, and which is huge one, is immigration.

A key contributor towards economic growth in Australia has come from immigration. It is pretty hard to argue otherwise. But the question is, what is a level that is sustainable?

From a numbers perspective, before pandemic, the government was maintaining a level of immigration equating to roughly 219,663 people each year.

Things obviously took a turn during the pandemic thanks to the border closures. This meant that only 6,866 immigrants were reported arriving by December 2021.

So, since last year, the government has been playing catch up and tweaking policies to allow plan for 195,000 immigrants in between 2022 and 2023, and a forecasted 190,000 immigrants over the next three years.

Here’s the thing though – over 400,000 migrants arrived in 2022 alone.

Many of these new arrivals are expected to be students, with ABS figures showing 253,940 students arrived at the end of this financial year.arriving by the end of FY23.

This is the largest international student intake on record, and equivalent to 101,576 new households forming. And certain interest groups aren’t holding back on their criticism.

They’ve argued that a large portion of student housing demand is “unaccounted for” and Australia’s stock of housing simply won’t be able to cope.

It’s estimated that 70% of new housing units supplied to the market over the last financial year were taken up by international students, leaving only 30% for the rest of the country, including other new migrants.

This has put an enormous amount of pressure on the availability of rental accommodation, rapidly forcing rental costs to surge, which also spills over to demand for buying.

So, ultimately, while sustainable immigration is healthy for economic growth, many have criticised the Government for allowing higher levels of immigration compared to what was originally forecasted pre-pandemic.

3. Australians’ Lifestyle Preference

One other pretty big demand driver is our cultural demand for “space” and “lifestyle” in Australia.

We have a general tendency to resist “vertical living” within the city centre – with many preferring the lifestyle of middle-ring and outer ring suburbs.

This has led to an aversion towards high-density living, which means cities are much more spread out compared to our overseas counterparts.

And of course without more density, and only so much “liveable” land, we drive the demand up along with the property prices.

What also happens is that the land component of property becomes more valuable – driving the prices up even further.

You can see this by looking at the massive difference in the increase in the price of houses versus units.

Over a 30-year period, house values in Australia’s capital cities have increased by 4.5 times to nearly $930,000, while unit values have only tripled to just over $635,000.

If we compare this to the less populated regional areas, the figures are slightly different, but it paints the same picture. House prices have tripled to around $623,000 and unit values have doubled to around $520,000 over the same period.

And I’m sure it comes at no surprise that the growth in land value has far exceeded the growth in incomes.

It takes about 10 years to save up the average 20% deposit, which, by the way, is 1.5 times the average full-time earnings. Whereas in 2001, it would’ve taken you around 6 years.

And if I add another layer to this and look at the stats in relation to the higher interest rates, the national estimate of median income required to service a new mortgage is now at a record high of 45.5% of income, compared to an average of 34.5% in 2010.

So, no – you’re not just imagining it. It is most definitely more expensive to buy a house today, than it was 10/20 years ago.

But, the harsh reality of it is that high property prices are also a result of the choices we make as a society. Our government, which we vote in, have all made certain choices that have led to high land and house costs.

4. Australia’s Tax Regime

The final demand driver which we will look at is our taxes.

Many argue that reforming taxes such as stamp duty and negative gearing, capital gains tax, stamp duties and land taxes could dramatically assist with housing affordability. However, messing around with our established tax frameworks is not a popular move for politicians.

This is a big topic in itself so I am going to keep this brief. Let’s just look at negative gearing which Australians have been using to lower their effective tax rate.

Negative gearing reduces the holding costs of investors who borrow to invest and thus keeps properties in the hands of the wealthy. This then arguably boosts demand for investment properties artificially.

But the question is, will reforming this tax lower property prices and if so by how much?

Research by the Grattan Institute has shown that limiting passive investment losses so they can’t be written off against wage income would lower property prices by of up to 2% lower. This economic modelling also takes into account a reduction in the CGT discount from 50% to only 25%.

I won’t judge whether 2% is big or small, but the impact is nowhere near the level put forward by commentators.

In the next post, I will then look at the other side of the equation, namely, the supply drivers. Please stay tuned!